Commentary on the Dharma Messages of Reverend Shigeaki Fujitani

By Pieper Toyama

We have the honor of presenting on the Jikoen website, fourteen Dharma Messages by Reverend Shigeaki Fujitani. Most of the messages were delivered while he was resident minister of Makawao Hongwanji in 2000.

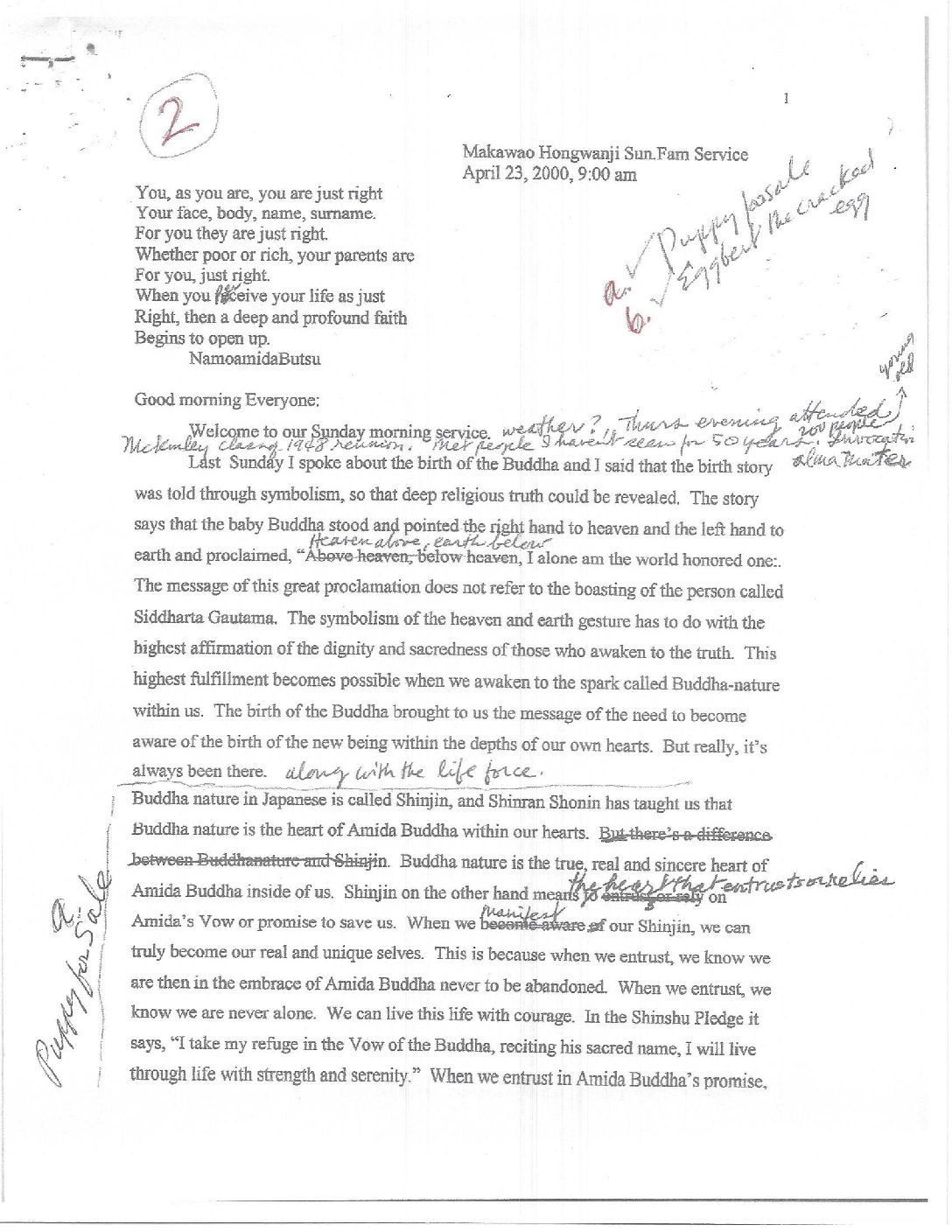

As I prepared his Dharma Messages for the website, my first plan to was to retype all of the original messages and include in the final copies the corrections and edits that Reverend Fujitani made. I was planning to post clean copies of all of the messages. I even started typing the first few messages. But as I read them as I typed, I realized that I was seeing something extraordinary. I was getting a glimpse into Reverend Fujitani’s mind as he developed his messages, how he organized his thoughts, and how he refined his expressions. With that realization, I knew that I had to share the messages exactly as they were given to me so all could see the process of how one minister went about preparing for his Sunday Dharma Message.

I was struck by a number of features and practices that made his Messages interesting, informative, relevant, and touching. Let me share my observations.

• The first thing I noticed was his use of stories. Sometimes he drew on the stories that are a part of our culture and our lives. He used fairy tales such as the Ugly Duckling, from Hans Christian Anderson (Message 4), and children’s stories such as Charlotte’s Web. Reverend Fujitani was fearless. He even drew from world literature when he shared the story of Faust by the German author, Goethe. In fact, he quotes Goethe in Message 13. But most of his stories were drawn from the vast resources of Buddhist stories. He tells stories of Shakyamuni Buddha, Shinran, and the myokonin, Genza who finds the reality of Amida’s love and compassion in his daily life.

His stories captured my attention because they were often told in great detail as in Message 3, when he unfolded the story of the boy with the face of a toad and the leper.

• My second observation was Reverend Fujitani’s willingness to draw upon the wisdom of those outside of the community of Shin Buddhists. He spoke of the Dalai Lama and even the Anglican priest, John Newton, who wrote Amazing Grace.

• The third thing that impressed me about his Dharma Messages is his attention to delivery. In Message 6, you can see how he marked each sentence where he would pause to help the listener comprehend his message more easily. This means that Reverend Fujitani must have read his Messages over and over out loud to figure out just where the pauses worked best. Such was his caring and sensitivity for his members who listened to him every Sunday.

• A fourth observation is the work Reverend Fujitani put into refining and organizing his Messages. I urge you to take the time to see how he made corrections and additions. Sometimes he deleted whole sections. Also note how he wrote on yellow Post-it notes the general outline of his Messages. His Messages were carefully thought out and put together. He knew exactly where he was going and how he was going to get there.

There are many ways to prepare and write Dharma Messages. Reverend Fujitani’s approach was to place the teachings into stories to which we can all relate, stories that were interesting, and stories that touched our hearts. I thank Reverend Fujitani for sharing his Dharma Messages so we can all enjoy not only its contents but also the process from which his Messages flowed.